Motivation Over Everything

First and foremost, the motivation to learn is much different between adults and children. Adults want to learn what they’re there to learn just so long as they can be convinced of the immediate value the learning has to their life. Once that intrinsic motivation is locked down, they just need structure, guidance, interaction, and feedback. It feels more like training.

With kids, it’s different. The main motivators are extrinsic and are based on a system of carrots and sticks. As a result, they need scaffolding, engagement, and reward to stay motivated. Almost as if learning is gamified. They have to consistently be in an area of desirable difficulty in order to want to continue. Otherwise, it just feels like school. Lev Vygotsky called this the Zone of Proximal Development. But keep in mind, this zone also extends to adults even though they are much more self-regulated in their learning.

To put it into simple terms, no matter what age you are, if you want to get somewhere and think you can catch the bus, you’ll run for it. So, a key to the motivation to learn in both adults and children, you have to meet them where they are in order to get them where they need to be. They just happen to be in different places.

A Primer on Schema Theory

Now, how children learn as opposed to how adults learn is a topic in constant debate between cognitivists and constructivists. However, a theory pretty much universally accepted is Schema Theory.

“Schema” is a fancy word for a cluster of information that makes up a concept or cluster of concepts inside the mind which enables us to make sense of the world outside the mind. A schema for a horse, for example, is made up of ‘large’, ‘animal’, ‘muscular’, ‘fast’, ‘long face’, ‘work’, ‘manure’, ‘hooves’, ‘fur’, ‘tail’, ‘four legs’, and so on, etc. It’s kind of like an internal mind map that just keeps expanding. Dense in some areas, thin in others.

When a schema is challenged by new information, we react in one of three ways—create additional schemata to accommodate the new info; alter our current schemata to assimilate the new info; or, we reject the new info based on how abstract or concrete it is and whether or not it confirms or contradicts our values.

So, if we only had a schema for horse and we saw a cow, we’d go: “oh what a weird looking horse”. At that point, someone would say: “no, dude, that’s a cow”. Then we would accommodate by making a new schema for cow that just so happens to share characteristics with our schema for horse. As such, our schema for animal would grow. If we saw a miniature horse, like a Shetland pony, we would add that new info to our existing schema for horse. And thus the knowledge base is widened and we can make more associations to make sense of what is otherwise unknown to us in the world, and so on and so forth.

There are a lot of different types of schemata. The example above was an ‘object’ schema. But these spiderwebs of associations can be centered around any idea or concepts. For example, a social behavior, the view of one’s self, physical processes, or a type of event. There are schemata in your mind for just about anything. And those schemata have a massive impact on how we learn.

So, How Do Adults and Children Differ When It Comes To Schema?

Here is where adults and children are different— Adults have tons of schemata to fall back on to make sense of new information; children don’t have nearly as many because they have had fewer experiences. In effect, children learn in a way where they constantly create new schemata while adults learn in a way where they constantly adjust or maintain existing ones.

However, the more schemata a person has and the longer they’ve had them, the harder it is for them to update them if they are conceptual inaccurate. Children are more plastic in that sense while adult learners are more rigid. An adult’s experiences, values, and beliefs take precedent over whether or not new information is true or useful. Children just absorb information because they’re still developing their values and beliefs as they collect experiences and create new schemata. In this respect, it’s much harder for children to extend their new knowledge to different contexts whereas it’s much harder for adults to let go of outdated ideas or misinformation.

Implications for Teachers of Adult Learners

An adult learner’s background is a juggernaut indicator of their existing schemata. Given that concrete examples best work to update existing knowledge, when dealing with a mixed bag of adult learners those examples must be many and varied. But amount and variety isn’t enough. The order in which concepts and examples are presented, and the way in which learners connect them, is paramount.

Much of the time, instructors introduce abstract concepts an then explain them with some concrete or worked examples. This is sometimes followed by an activity designed to lend experience to those abstract ideas. Although this feels intuitive, it is very much a mistake. All learners—adults and children alike—need to form episodic memories before they can fully form semantic ones. That is to say, we absorb information in the concrete world of experience and then we process it in the abstract world of thinking.

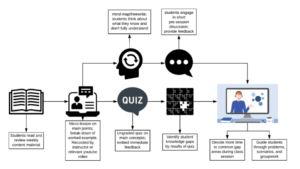

What follows is a recommended lesson plan for teaching a new set of concepts to a diverse set of adult learners. This sequence is designed to activate prior knowledge which is then immediately applied to deep processing (identifying how disparate things can connect). This calls upon existing schemata to make sense of things while simultaneously updating those schemata with concrete yet novel information. Finally, the examples are drilled down to the abstract concepts beneath.

This allow students to incorporate new concrete information into their existing knowledge base before they reorganize that information into a more refined schema. They use what they already know to intuit the nature of what they don’t. Only then, when they are shown the explicit abstract concepts, will they begin to consciously connect the concrete to the abstract.

10 Step Lesson Plan for Adult Learners